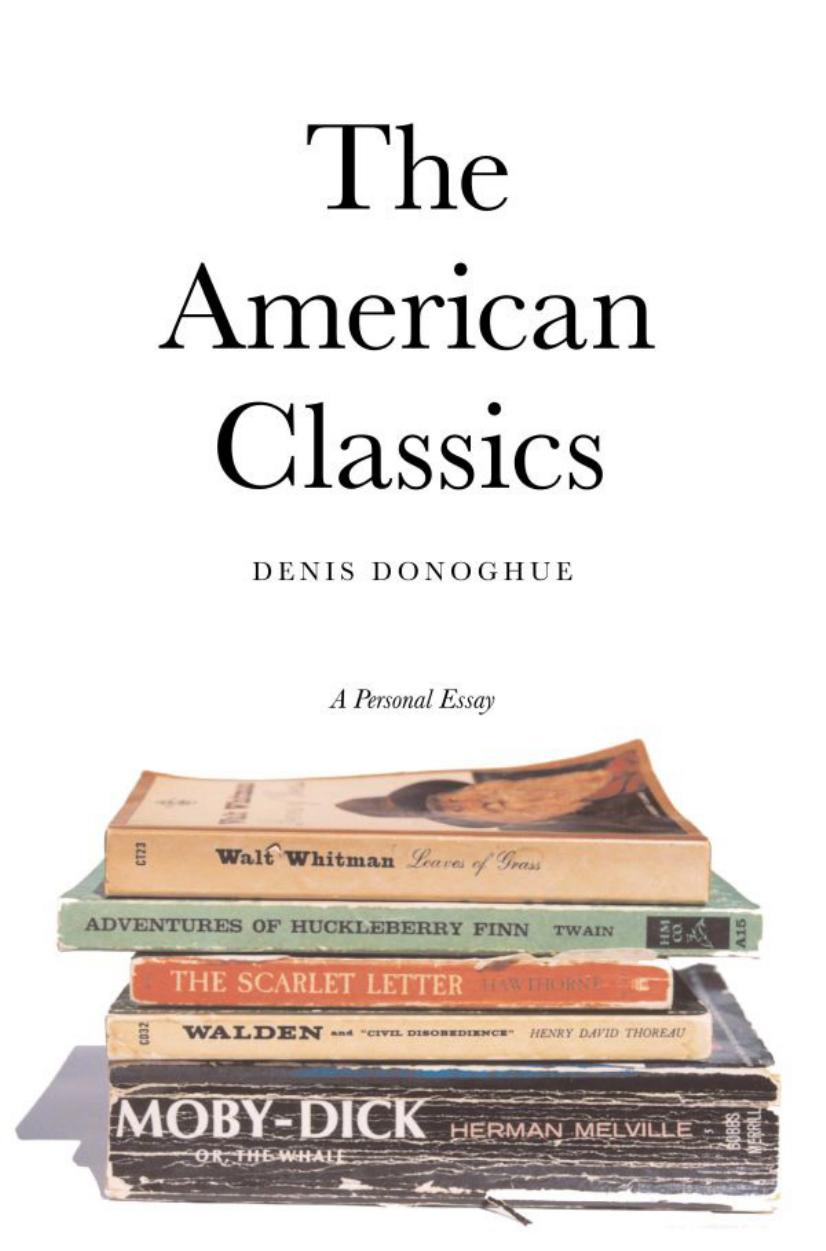

The American Classics by Denis Donoghue

Author:Denis Donoghue

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2014-02-12T16:00:00+00:00

2

If Walden and the other books constitute, as I suggest, Thoreau’s “song of myself,” we need to trace its coordinate terms, beginning with his god-term. Like Emerson, Thoreau tended to speak of God when he had to recognize a fact of life and the world that he could not think of as an effect without a cause. He could not regard the universe as a spontaneous entity without attribution. I am not equating Emerson and Thoreau in this respect. When Emerson gave up his ministry, he retained (as I have claimed) a somewhat more religious sensibility than Thoreau did, short of holding to anything much in the way of a theology. But Thoreau acknowledged a quasi-personal divine power even when he was not required by the argument to do so. In the “Spring” chapter of Walden he is merely wondering why one side of a cut on the railway is covered with foliage and the other is not, but “I am affected,” he says, “as if in a peculiar sense I stood in the laboratory of the Artist who made the world and me,—had come to where he was still at work, sporting on this bank, and with excess of energy strewing his fresh designs about.” In the “Solitude” chapter Thoreau says that “Next to us is not the workman whom we have hired, with whom we love so well to talk, but the workman whose work we are.” In the “Conclusion,” quoting the last verses of Claudian’s “De Sene Veronensi”—

Erret, et extremos alter scrutetur Iberos.

Plus habet hic vitae, plus habet ille viae—

Thoreau changed Iberos (Spaniards) to “Australians,” making the reference more applicable to his own time, and he changed “plus ... vitae”—“more life” —to “more of God,” even at the cost of removing Claudian’s play of words between “vitae” and “viae.”19

But generally Thoreau did not like people enough to give them the dignity of seeming to be a little like the creative God. So he spoke of God, for the most part, as an algebraic value, necessary by definition and to be acknowledged in practice but not otherwise to be commented on. Thoreau assented to God by acknowledging Life and ignoring whatever differences between those values a more strenuous theology would insist on. He managed to do this by thinking of life as a gift from an anonymous donor. Gratuitousness was the quality most to be appreciated: hence, as Sharon Cameron says, “Man is in the natural world as its witness or beholder, not as its explicator.”20 What we witness or behold is life as manifested, which Thoreau—like Emily Dickinson—sometimes called immortality:

Ah! I have penetrated to those meadows on the morning of many a first spring day, jumping from hummock to hummock, from willow root to willow root, when the wild river valley and the woods were bathed in so pure and bright a light as would have waked the dead, if they had been slumbering in their graves, as some suppose. There needs no stronger proof of immortality. All things must live in such a light.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12391)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7763)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5775)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5771)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5447)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5096)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4943)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4731)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4574)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4556)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4540)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4448)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4106)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4031)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4009)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3986)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3852)